Over the last two decades, Dr. Yasir Qadhi has undergone a visible transformation—from a well-known Salafi da’wah figure trained in Madinah to a confused pseudo academic whose public statements reflect the doubts and methods of Western secular scholarship. This shift reflects a broader pattern among Muslim intellectuals who engage with the modern academy: what begins as curiosity often becomes admiration, and what begins as dialogue ends in surrender..

To understand this transformation, I use the framework developed by Frantz Fanon, a 20th century theorist of colonial psychology. I end this essay by contrasting Qadhi with another figure who also engaged Western academia but without compromising his roots.

Frantz Fanon and the Problem of the Colonised Intellectual

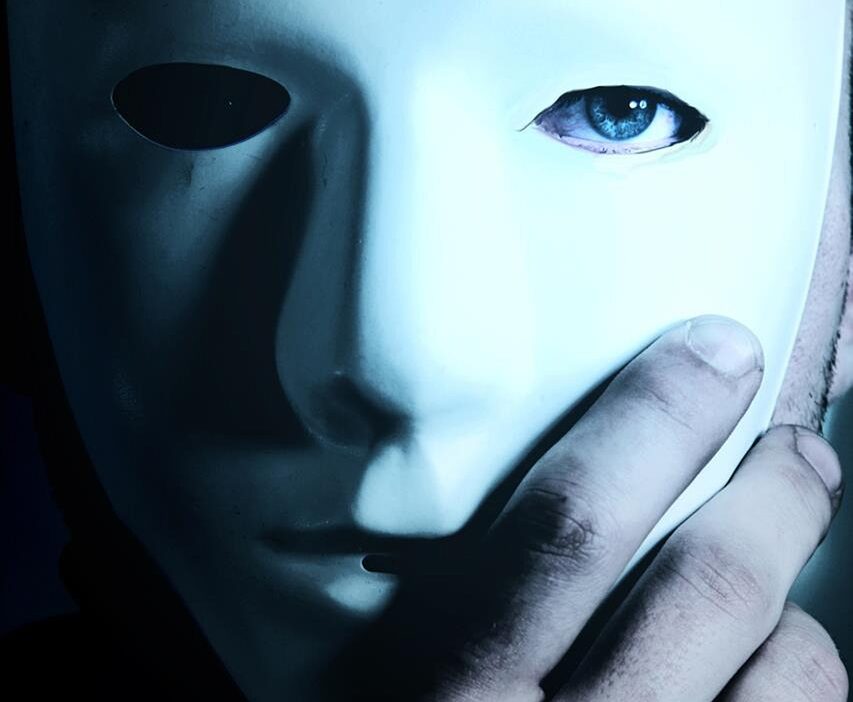

Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks explores how colonised people try to gain respect in Western society. Fanon argues that many of these people especially the educated ones begin to act, speak, and even think like their former colonisers. They adopt what Fanon calls a “white mask” not literally, but intellectually. They hide their discomfort with their own identity by embracing the worldview, values, and validation of their former masters.

Instead of building on the knowledge and tradition of their own people, they praise the theories of outsiders. They imitate the language, methods, and attitudes of the coloniser. But by doing so, they begin to look down on their own people, traditions, and religion. In trying to fit in, they become alienated from their roots, their faith, and even from themselves. Though Fanon’s work is set in the context of racial colonialism, his framework fits well with the case of Dr. Yasir Qadhi, who transitioned into Western academia and now embodies the intellectual schizophrenia Fanon warned against.

In Qadhi’s case, it is not about skin colour but Western orientalism. His claim that Western academic work is superior to Islamic scholarship reflect what Fanon called the wearing of the white mask. When Qadhi says,

“ (when) you read this type of [Western academic] stuff and not only do they do a better job and [are] more accurate, they also go far more detailed…. there is nothing equivalent.“” he is treating Western secular methods as the gold standard for truth.

This is the mindset Fanon warned against: one that craves validation from the coloniser and loses confidence in its own tradition. Fanon says the colonised intellectual wants to be accepted as “reasonable” and “civilised,” so he begins to reject the teachings of his own culture if they are seen as backward or unscientific. This desire for acceptance, for being taken seriously in secular circles, leads the colonised intellectual to reinvent himself in the image of the coloniser’s ideal: a native who rejects his roots and presents himself as a neutral, objective critic of his own tradition. For Fanon, such behaviour is not genuine self-examination but internalised self-hatred.

Qadhi’s trajectory echoes this in a striking way. Over time, he has moved away from the entire Sunni intellectual tradition. In its place, he has adopted a perspective shaped by Western academic critiques of Islam: assumptions of textual evolution, historical scepticism about the Sunna, and rejection of theological certainty. Islam is no longer lived and defended—it is submitted to the court of secular judgment.

Yale as the Site of Transformation

Qadhi’s transformation is most visibly marked by his time at Yale. He admits: “Wallahi, I’ll be honest with you, the shubuhāt (doubts) that I was exposed to at Yale, some of them I still don’t have answers for.” He recalls reading Josef van Ess, a German Orientalist, and “almost literally drooling” over his work. A non Muslim scholar becomes, in his eyes, the definitive voice on Islamic theology, while centuries of Muslim thought are implicitly diminished.

Qadhi’s time at Yale marked a major shift in how he thinks and who he aligns with. He came out with a new outlook and sense of loyalty. He had begun to see the world through the lens of the coloniser.

Public Faith, Private Doubt: Preacher vs. Academic

Qadhi has publicly confessed to living a double intellectual life: “When I become Sheikh Yasir, I will quote Sahih Bukhari… that’s the preacher. In the academy, I cannot quote Bukhari and [assume] this will be [considered] what the Prophet ﷺ said.” Islam is a subjective faith, while Western skepticism is treated as neutral, scientific, and authoritative.

Qadhi adopts Western academic standards as the benchmark for what counts as credible. Sunni scholarship is no longer treated as a complete and authoritative system in its own right, but as something that must be filtered, dissected, and reevaluated through a secular lens. This shift becomes even more apparent in how he frames Islamic theology.

Rather than viewing ʿaqīdah as divinely revealed truth preserved by the Salaf, Qadhi describes it as a set of evolving human attempts to answer questions shaped by “cultural and socio-political factors.” He argues, by way of example, that the Sunni affirmation of Allah’s attributes such as affirming that Allah has a “hand” was a back projection onto the Sahabah, influenced by historical debates with groups like the Muʿtazilah. “The Sahaba didn’t say like this,” he insists. “We don’t know what they actually believed, right? We really don’t know, we’re just assuming.”

This framing mirrors the Western historical critical method applied to Christianity, i.e. that Christian beliefs evolved over time and that we can never truly know what ʿĪsā (peace be upon him) or his disciples originally taught. Qadhi now imposes this same method onto Islam. He no longer sees Islam as a complete and preserved tradition but assumes it has evolved in response to external pressures just like Christianity or Judaism.1

Yet this assumption collapses under scrutiny. It rests on a false equivalence between Islam and the corrupted trajectories of earlier religions. It assumes that if the early Muslims did not use a particular phrase, they must not have held the belief it expresses. While it’s true that the Ṣaḥābah didn’t use abstract theological terms, this was simply because they had no need to—no one in their time denied Allah’s attributes.2

Sunni scholars have long recognised the influence of political, social, and philosophical pressures on deviant sects. But the ʿaqīdah of Ahl al-Sunna was never the product of these forces it was a preservation of what the Prophet ﷺ taught and what the Companions believed. The later terminology that emerged was not an innovation in creed, but a defense of existing truths in response to emerging heresies.

For example, Imam ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Mubārak (d. 181 AH) stated, “We know that our Lord is above the heavens, upon His Throne, distinct from His creation.” The Sahaba didn’t use this precise phrasing because no one in their era denied Allah’s highness. Ibn al Mubārak’s words didn’t introduce something new but defended an already understood truth, now explicitly stated to refute innovators like Jahm ibn Ṣafwān.

Yet Qadhi argues that even this was unnecessary. In his view, the entire ṣifāt controversy is not really theological at all, but a linguistic misunderstanding. He claims it can be resolved through modern European theories of language particularly those of Wittgenstein. What the Salaf treated as essential belief, he reduces to semantics. The centuries of refutation and clarification by scholars like Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal and Ibn Taymiyyah are, in hindsight, framed as misguided responses to confusion over words. If only, it seems, they had access to the insights of modern Western philosophy, (as Dr. Qadhi does) the controversy could have been avoided altogether.3

Yasir Qadhi – the Brown Sahib

This concern about internalised Western superiority is deepened further by the work of Ziauddin Sardar. In his influential book Orientalism (1999), Sardar extends Edward Said’s critique by showing how Orientalism survives and evolves within modern academia. Islam is still treated not as a living tradition but as a system of texts and doctrines to be dissected, explained, and judged through Western categories. In this process, Muslims are turned into objects of study, spoken about, but not listened to.

This diagnosis fits perfectly with the way Qadhi performs in academic circles mimicking Orientalist scholarship while serving as a convenient native informant for its anti-Muslim agenda. When he declares that the Western academy has “proven beyond reasonable doubt” that the Qur’an exists in an ‘Uthmanic recension, but we cannot say the same for hadith, the implication is that the real standard of truth lies outside Islam. Revelation must pass the test of Western historical methods and if it does not, it is no longer treated as knowledge.

Qadhi’s rhetoric reflects a deep inferiority complex and a need for approval from the very institutions that undermine Islam. This mindset lies at the heart of what Sardar calls the “Brown Sahib” someone who sees himself and wants to be see as a mirror of the colonizer. The Brown Sahib is a believer in Western superiority, convinced that progress requires disowning his own tradition, he believes that Islam must be reframed through Western categories in order to be respectable. It is a legacy of colonial thinking, best captured in Macaulay’s infamous 1835 statement.

“We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.4”

Sardar describes how colonial systems deliberately manufactured such figures through education systems that divorced them from their own cultures and made them ashamed of their traditions. The goal was never just physical control but intellectual dependency. This colonial mindset persists in the native informant who speaks not for Islam, but for the West’s view of Islam. Yasir Qadhi increasingly plays this role with remarkable precision. He has become the sort of “interpreter” Macaulay hoped for: native in blood, but Western in intellect. Sardar may not have had Qadhi in mind when describing the “Brown Sahib,” but the shoe fits so well it might as well have been tailor made.

Al-Aʿẓamī Unmasked Orientalism—Qadhi Surrendered to It

Professor Muṣṭafā al-Aʿẓamī (d. 2017) is a powerful example of a scholar who remained firmly rooted in traditional Islamic knowledge while also mastering the tools of Western academic research.5 His famous book Studies in Early Hadith Literature is not just a defence of the Sunnah, it is also a thorough refutation of Western Orientalist attacks on the hadith sciences.

Al-Aʿẓamī was classically trained in the madrasa tradition, memorising Qur’an, studying with leading ḥadīth scholars in India, and later training at al-Azhar. Yet his PhD from Cambridge University, praised by his examiner Professor A.J. Arberry as “one of the most exciting and original investigations in this field of modern times,” showcases his ability to operate within Western scholarly standards. Unlike Qadhi, Professor Al-Aʿẓamī did not use his academic training to undermine Islam. Instead, he used it to expose the weaknesses in the arguments of Orientalist scholars like Ignaz Goldziher and Joseph Schacht.

Using Western historiographical tools, al-Aʿẓamī was able to affirm the normative Sunni view that hadith literature, far from being a later fabrication, was systematically preserved from the earliest generations. He also shows that the hadith sciences were developed early on, with rules of narrator evaluation and isnād criticism that rival any Western historical method in precision and care.

Unlike Qadhi, Professor al-Aʿẓamī not only mastered the tools of Western Orientalism particularly in areas like hadith criticism and historiography but critically assessed them from within the Islamic paradigm. He engaged Western methods without being intellectually subdued by them. He saw their limitations, exposed their biases, and used them to strengthen the Islamic tradition rather than undermine it. Qadhi, on the other hand, did not merely borrow these tools he embraced the entire Orientalist framework that produced them. The brown sahib that he is, Qadhi failed to critically dissect the assumptions of Western scholarship, assumptions that even non Muslim thinkers like Edward Said and Frantz Fanon recognised and challenged. Instead of questioning the lens, he looked through it. He did not see Orientalism as a colonial enterprise of intellectual domination, but as a path to enlightenment. In doing so, he became its archetype: the native informant, fluent in the language of doubt, alienated from the tradition he once claimed to defend.

Conclusion

The case of Yasir Qadhi illustrates Fanon’s warning in full. The colonised intellectual, the brown sahib eager to appear reasonable to his masters, sheds his own tradition piece by piece until nothing remains but a mask. What began as engagement ends as erasure. And in this erasure, Qadhi no longer speaks for Islam but for the West’s version of it. He has worn the coloniser’s mask for so long, he no longer knows what his own face looks like..

Also see this article.

References

Azami, Muḥammad Muṣṭafā. Studies in Hadith Methodology and Literature. Indianapolis: American Trust Publications, 1977.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. Richard Philcox. Grove Press, 2008.

Sardar, Ziauddin. Orientalism. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1999

Tibawi, A.L. English-Speaking Orientalists: A Critique of Their Approach to Islam and Arab Nationalism, Islamic Quarterly, 1964–1979.

Zawadi, Bassam. A Review of Dr. Yasir Qadhi’s “Advanced Aqidah” Course, 2020.

Abdul Rahman (TAP). “Twitter commentary on Yasir Qadhi’s epistemology.” July 16, 2025. https://x.com/abdul_now/status/1945466670656442447

Yasir Qadhi. YouTube lecture: “The Standard Narrative Has Holes In It.” June 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39w6g_Bf_UI&t=1s

EXPOSED: The Confused Epistemology of Dr Yasir Qadhi. The Rabbit Hole – with Abdul Rahman (TAP) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWzRd2ICF8s&t=714s

- The ramifications of this approach are starkly evident in specific instances of his controversial positions:

Yasir Qadhi explicitly casts doubt on the perfect preservation of the Qur’an, stating that the “standard narrative has holes in it”. And “The preservation must be interpreted in another manner.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39w6g_Bf_UI&t=1s

“How can we then understand the Qur’an as being Kalaam Allah (the speech of Allah) when clearly there are human aspects to it.”

He claims that the Shar’i punishments (hudud) are not meant to be implemented, but were revealed by Allah merely as “scare tactics,” asserting it’s an “ongoing discussion” to modify and modernize these divine laws. He even refers to some of these laws, such as stoning, as “bizarre”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zD-zJsY2sEYhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zD-zJsY2sEY

Denies belief in Yajuj and Majuj https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39w6g_Bf_UI&t=446s

On supporting same-sex marriage: “Politically yes… morally I don’t.” ↩︎ - Taken from EXPOSED: The Confused Epistemology of Dr Yasir Qadhi, an episode of The Rabbit Hole podcast hosted by Abdul Rahman (TAP). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWzRd2ICF8s&t=714s (accessed July 2025). ↩︎

- Abdul Rahman (TAP) demonstrates how Qadhi misreads both the early and late Wittgenstein, wrongly treats theological debates as linguistic confusions, and ultimately collapses theology into relativism undermining the very tradition he claims to represent. ↩︎

- This quote is taken from a speech by Thomas Babington Macaulay, a British politician and historian, in his 1835 “Minute on Indian Education.” Macaulay was a key figure in shaping British colonial education policy in India. In this document, he argued for replacing traditional Islamic and Hindu education with English-language instruction rooted in Western thought. His aim was to create a class of Indians who would act as intermediaries between the British rulers and the wider Indian population—people who were Indian by ethnicity but intellectually and morally aligned with British colonial values. This policy helped produce a generation of colonised elites who viewed their own traditions as inferior and sought legitimacy through Western approval. cited in Sardar p.86 ↩︎

- He served as Professor of Hadith Studies at King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.He was also a visiting scholar at several Western universities, including the University of Michigan, the University of Colorado and the University of Oxford. He authored several landmark works, including Studies in Hadith Methodology and Literature, On Schacht’s Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, The History of the Qur’anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation, and The Qur’an and the Orientalists: An Examination of their Main Theories and Assumptions. ↩︎